What is Potassium?

Potassium is a fundamental mineral and electrolyte found inside your cells. It carries a positive charge and works in concert with sodium to manage fluid balance, nutrient transport, electrical impulses in nerves, and muscular contractions.

Why does it matter for long-term health and wellbeing?

Because of its central role in cellular energy, nerve–muscle communication and fluid balance, potassium is intimately tied to overall physiological performance and resilience. In population research, higher potassium intake is linked with improved vascular tone, moderated sodium load effects and lower incidence of circulatory stress over time. In essence, stable potassium levels support the kind of metabolic equilibrium that underpins longevity and vitality.

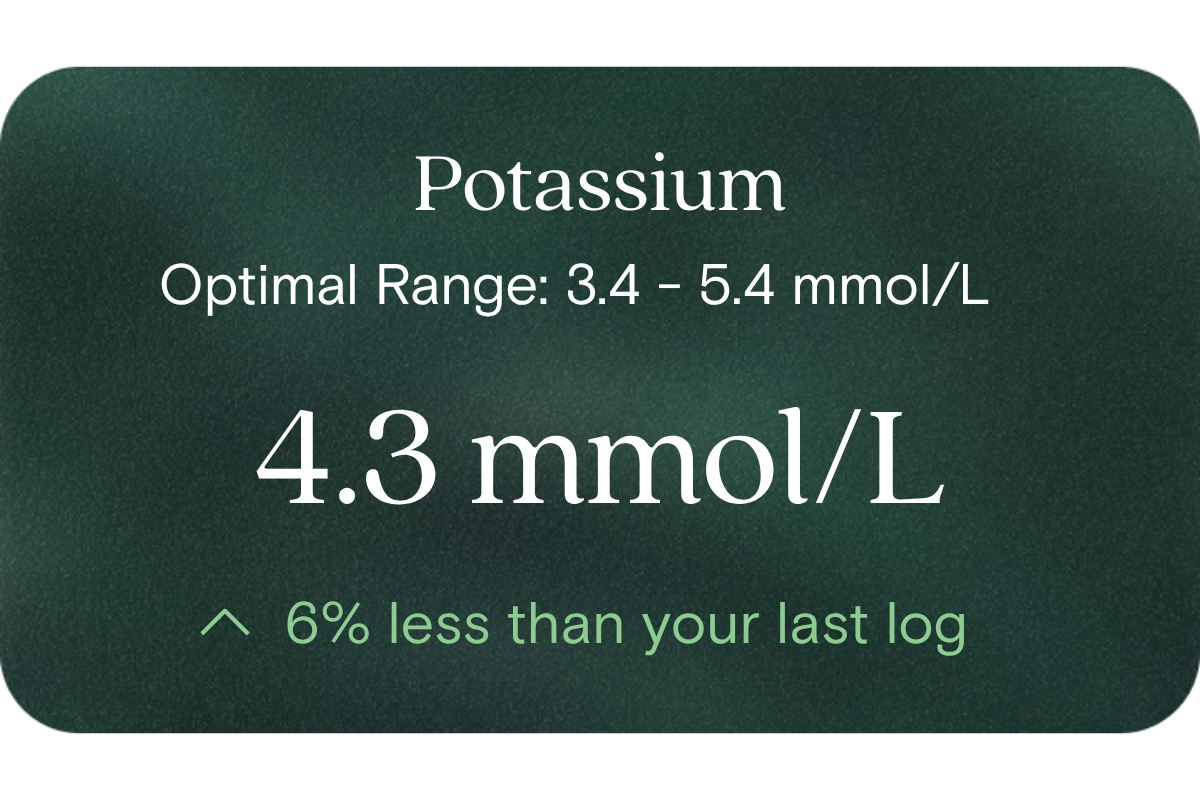

What’s an optimal level of Potassium?

- Laboratory reference range (Australia): 3.6 to 5.4 mmol/L (blood serum)

- Optimal (performance / balance target): Many practitioners aim for values comfortably mid-range to slightly above midpoint — for example ~ 4.0 to ~ 5.0 mmol/L — as this tends to reflect good balance without pushing toward extremes

These ranges reflect general population norms and ideal zones for sustained physiological function.

What influences Potassium levels?

Several lifestyle and environmental factors impact potassium:

- Dietary intake (especially from whole foods such as leafy greens, legumes, root vegetables, fruits, dairy)

- Hydration status and fluid losses (sweating, dehydration, vomiting or diarrhoea)

- Sodium intake and the sodium:potassium balance — high sodium can drive potassium losses

- Hormonal and kidney handling (kidneys filter and excrete excess potassium, while hormones such as aldosterone influence secretion)

- Medications or supplements (that influence electrolyte handling or urine output)

- Cellular shifts (changes in pH, insulin or other metabolic shifts can move potassium into or out of cells)

What does it mean if Potassium is outside the optimal range?

- If potassium is creeping toward or below the lower part of the reference range, this might suggest under-consumption, increased losses, subtle shifts in kidney regulation or mild cellular stress. It might manifest (in extreme cases) as reduced muscular efficiency or fatigue.

- If potassium is drifting toward the upper end or beyond, it can indicate impaired excretion, excessive cellular release, or altered electrolyte regulation. While not a problem in itself in many cases, an upward trend may warrant attention to kidney buffering, medication interactions or mineral load imbalances.

In either case, deviation is best treated as insight rather than urgent alarm — a prompt to review diet, hydration, recovery and renal support strategies.

How can I support healthy Potassium levels?

- Prioritise whole-food sources rich in potassium: leafy greens, beans and legumes, root vegetables (sweet potato, potato), fruit, dairy and nuts

- Maintain balanced sodium intake and focus on the sodium:potassium ratio rather than eliminating salt entirely

- Stay well hydrated and manage fluid losses especially during heat, heavy sweating or extended exertion

- Monitor medication or supplement interactions (e.g. diuretics, supplements) in consultation with professionals

- Spread intake across meals to avoid sudden spikes or shifts

- Use serial testing (e.g. quarterly or semi-annual) to track trends and adjust your nutrition and hydration strategies based on data

This information is provided for general health and wellness purposes only and does not replace medical advice.

References

- Eat for Health. (2024). Nutrient Reference Values – Potassium. National Health and Medical Research Council.

- Healthdirect Australia. (2024). Potassium and your health.

- Royal College of Pathologists of Australasia. (2024). RCPA Manual: Potassium.

- Weaver, C. M. (2018). What is the evidence base for a potassium requirement? Advances in Nutrition, 9(6), 695–706.

.png)

.svg)