Choose how you’d like to begin

CGM program

Optimise metabolism in real time with sensors

Advanced Blood Test

Get your baseline health report and personalised plan

Artificially sweetened “diet” sodas have long been touted as a safer alternative to sugary drinks, especially for people watching their weight or blood sugar. In fact, UK health advice notes that approved low or no-calorie sweeteners are considered safe substitutes for sugar and can help reduce sugar intake.

However, emerging research suggests a surprising link: frequent consumption of diet soft drinks may actually increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. A major Australian study found that adults who drank one can of diet soda a day had a 38% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to non-drinkers, even higher than the 23% increased risk seen in those who drank sugary sodas daily.

This blog unpacks the evidence behind this counterintuitive finding, explains possible reasons, and offers practical guidance.

Most people know that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) like regular cola, lemonade and energy drinks are linked to weight gain and diabetes. Indeed, meta-analyses show that people with high intake of sugar-sweetened drinks have roughly a 30% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Health guidelines worldwide (including UK NHS advice) urge us to cut down on added sugars for this reason. Diet drinks, sweetened instead with artificial sweeteners (like aspartame, sucralose, acesulfame-K, etc.), were introduced on the assumption that they avoid the blood sugar and calorie load of sugar.

Short-term trials find that when people replace a sugary drink with a diet version, they often eat fewer calories and may lose weight, and there’s no clear evidence that sweeteners increase appetite.

On this basis, diabetes guidelines often suggest diet drinks are a better choice than regular soda. For example, one recent survey of people with diabetes noted that switching sugar drinks to diet sodas was associated with lower risk of death and cardiovascular disease.

However, in contrast to these beliefs, growing evidence from long-term studies is painting a more complex picture. The World Health Organization after reviewing the literature, even advises against using artificial sweeteners for weight control, stating there is no long-term benefit and possible harms, including an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

In practice, many people in Australia, the UK and elsewhere do rely on diet soft drinks for a sweet fix. In the EU, for instance, diet soda consumption rose from 23% of people in 2016 to 30% in 2021. It’s therefore important to understand whether these sugar-free options are as harmless as once thought.

Not sure which weight-loss shake is right for you? Discover our guide to the top options in Australia and find out how real-time metabolic tracking can show which one works best for your body.

A high-profile Australian cohort study (led by Monash University and published in Diabetes & Metabolism) suggests the risk of diabetes may be higher with diet drinks than with sugary ones.

Researchers followed 36,608 Australian adults (aged 40–69) for nearly 14 years. Participants self-reported how often they consumed sugar-sweetened or artificially sweetened beverages. After accounting for diet, exercise, education and health history, they found:

In other words, daily diet drinks appeared even more strongly associated with diabetes than daily sugared drinks.

These findings have attracted media attention worldwide. A recent press report summarised: “drinking just a single can of artificially sweetened soft drink a day… was associated with a 38 percent higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes”.

It pointed out that this was based on detailed records of 36,608 Australians over 14 years, and that this risk exceeded the 23% increase linked to sugar drinks.

Key takeaway: The Australian data suggest that long-term daily consumption of diet soft drinks may notably increase the risk of future type 2 diabetes.

This is a surprising result, because it runs counter to the idea that cutting sugar from your drinks automatically makes them “safe”. Importantly, these are associations observed in a study, not proof of direct causation, but the strength of the link, especially after statistical adjustment, raises concerns.

The Australian study is not an isolated case. Other large observational studies have reported similar associations between diet drinks and diabetes or metabolic disorders:

This was true even after adjusting for body weight and other risk factors (though diet soda’s link to metabolic syndrome components was partly mediated by weight gain).

Systematic reviews of such cohort studies tend to show a small but significant positive association between artificial sweetener intake and diabetes risk, although confidence is often graded as low due to study limitations.

These human studies cannot prove that diet sodas cause diabetes. It is possible, for example, that people predisposed to diabetes (e.g. already overweight) are more likely to switch to diet drinks, which could confound the findings (“reverse causality”).

That said, investigators in the Aussie study explicitly adjusted for body mass index and found the diet-drink link remained significant, suggesting it was not solely due to obesity. Similarly, the US MESA study found the diabetes risk from diet soda was independent of baseline weight or weight change.

Notably, some studies report that when you do adjust for weight, the effect for sugary drinks disappears but the effect for diet drinks does not. One news summary observed: “when body weight was factored in, the link between sugary drinks and type 2 diabetes disappeared – suggesting being overweight was driving that association.

[But] when body weight was factored into the artificial sweetener link, the increased risk was still present”. This pattern hints that diet drinks may influence glucose metabolism or diabetes risk through mechanisms other than simply promoting obesity.

Feeling like sugar cravings get the best of you? Dive into our science-backed breakdown on sugar and cravings to see what really drives them.

How might “zero-calorie” sweeteners raise diabetes risk? Scientists have several hypotheses, though the exact pathways remain unclear:

In short, the biological reasons for the observed link are not fully established. As ScienceAlert noted, “so many known contributors to type 2 diabetes” exist that researchers cannot yet say artificial sweeteners directly cause diabetes.

Indeed, a recent comprehensive review concluded that randomised trials and most systematic reviews have not provided definitive evidence that non-nutritive sweeteners raise diabetes risk.

This ambiguity led WHO to issue a conditional guideline: while the evidence suggests potential harms (like higher diabetes risk), it may be confounded by other factors. WHO therefore recommends reducing sweetener use as a precaution.

Struggling to understand how sugar affects your body? Discover the connection between sugar and insulin resistance in our latest guide.

Health agencies and expert bodies take a cautious stance:

WHO warns this may be due to confounding (“link may be complicated”), but nonetheless suggests that people should aim to reduce sweet tastes altogether.

In summary, while no health agency has banned diet sodas, there is growing caution. WHO’s advice highlights that “non-sugar sweeteners are not essential dietary factors and have no nutritional value” and that their long-term use could be harmful. The consensus message is moderation.

Given this uncertainty, experts now encourage people (especially those at risk of diabetes) to favour water and unsweetened drinks whenever possible. In fact, a recent clinical study presented at the American Diabetes Association meeting found that switching from diet soda to water dramatically improved outcomes for women with type 2 diabetes.

In that trial, 81 overweight/obese diabetic women were randomly assigned to replace their usual post-lunch diet soda with water (while all participants followed a weight-loss program). At 18 months, the water group lost significantly more weight and – most strikingly – 90% of them achieved diabetes remission, compared to only 45% of the diet-soda group.

This underscores the practical point: water is the healthiest drink choice. We embed an image below illustrating this principle.

Even if you enjoy sweet drinks, consider unsweetened options first (sparkling water with lemon, plain tea/coffee, etc.). If you do use artificial sweeteners, use them sparingly.

For diabetic individuals, the take-home is similar: one diet soft drink a day may not be harmless. It’s wise to monitor blood glucose closely and discuss drink choices with your healthcare team. Drinking plenty of water and cutting back on all sweetened beverages (sugar-free or not) is a safe strategy.

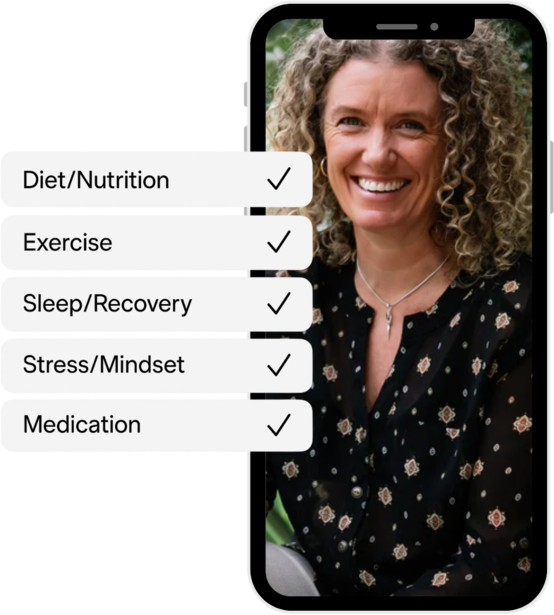

Cutting back on diet sodas is a positive step, but it’s just one part of managing blood sugar and long-term health. Vively gives you the tools to see the bigger picture of how your daily choices affect your metabolism.

With Vively you can:

By combining real-time insights from CGM with your personalised Wellness Score, Vively helps you move beyond assumptions about “healthy” alternatives and truly understand what works for your body.

“Many people assume that switching to diet soft drinks is a safe option, but the research shows it may not be that simple. At Vively, we help people move beyond the labels and see how their choices actually affect their body in real time. Our Wellness Score and CGM insights make it easier to spot patterns and build healthier habits that truly support long-term health.” — Charlotte Battle, Accredited Practising Dietitian & Lead Dietitian at Vively

In summary, while diet soft drinks were designed as a lower-risk alternative to sugary sodas, recent research suggests they are not risk-free. Large cohort studies from Australia, Europe and the US consistently report that habitual diet soda consumption is associated with a higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes.

The reasons are still under investigation, and causation has not been proven. Nevertheless, the finding is “surprising” to many health professionals. In light of this, health authorities advise caution: the WHO explicitly warns of potential harms (including raised diabetes risk) from long-term sweetener use, and leading experts now encourage water as the primary beverage for those at risk of diabetes.

For the general public and especially people with diabetes, the smart approach is moderation and awareness. Don’t assume “zero calories” means “zero consequences.” Limiting both sugary drinks and diet sodas, and choosing water or unsweetened beverages, is the safest bet for blood sugar control and overall health.

Subscribe to our newsletter & join a community of 20,000+ Aussies

Artificially sweetened “diet” sodas have long been touted as a safer alternative to sugary drinks, especially for people watching their weight or blood sugar. In fact, UK health advice notes that approved low or no-calorie sweeteners are considered safe substitutes for sugar and can help reduce sugar intake.

However, emerging research suggests a surprising link: frequent consumption of diet soft drinks may actually increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. A major Australian study found that adults who drank one can of diet soda a day had a 38% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes compared to non-drinkers, even higher than the 23% increased risk seen in those who drank sugary sodas daily.

This blog unpacks the evidence behind this counterintuitive finding, explains possible reasons, and offers practical guidance.

Most people know that sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) like regular cola, lemonade and energy drinks are linked to weight gain and diabetes. Indeed, meta-analyses show that people with high intake of sugar-sweetened drinks have roughly a 30% higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes.

Health guidelines worldwide (including UK NHS advice) urge us to cut down on added sugars for this reason. Diet drinks, sweetened instead with artificial sweeteners (like aspartame, sucralose, acesulfame-K, etc.), were introduced on the assumption that they avoid the blood sugar and calorie load of sugar.

Short-term trials find that when people replace a sugary drink with a diet version, they often eat fewer calories and may lose weight, and there’s no clear evidence that sweeteners increase appetite.

On this basis, diabetes guidelines often suggest diet drinks are a better choice than regular soda. For example, one recent survey of people with diabetes noted that switching sugar drinks to diet sodas was associated with lower risk of death and cardiovascular disease.

However, in contrast to these beliefs, growing evidence from long-term studies is painting a more complex picture. The World Health Organization after reviewing the literature, even advises against using artificial sweeteners for weight control, stating there is no long-term benefit and possible harms, including an increased risk of type 2 diabetes.

In practice, many people in Australia, the UK and elsewhere do rely on diet soft drinks for a sweet fix. In the EU, for instance, diet soda consumption rose from 23% of people in 2016 to 30% in 2021. It’s therefore important to understand whether these sugar-free options are as harmless as once thought.

Not sure which weight-loss shake is right for you? Discover our guide to the top options in Australia and find out how real-time metabolic tracking can show which one works best for your body.

A high-profile Australian cohort study (led by Monash University and published in Diabetes & Metabolism) suggests the risk of diabetes may be higher with diet drinks than with sugary ones.

Researchers followed 36,608 Australian adults (aged 40–69) for nearly 14 years. Participants self-reported how often they consumed sugar-sweetened or artificially sweetened beverages. After accounting for diet, exercise, education and health history, they found:

In other words, daily diet drinks appeared even more strongly associated with diabetes than daily sugared drinks.

These findings have attracted media attention worldwide. A recent press report summarised: “drinking just a single can of artificially sweetened soft drink a day… was associated with a 38 percent higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes”.

It pointed out that this was based on detailed records of 36,608 Australians over 14 years, and that this risk exceeded the 23% increase linked to sugar drinks.

Key takeaway: The Australian data suggest that long-term daily consumption of diet soft drinks may notably increase the risk of future type 2 diabetes.

This is a surprising result, because it runs counter to the idea that cutting sugar from your drinks automatically makes them “safe”. Importantly, these are associations observed in a study, not proof of direct causation, but the strength of the link, especially after statistical adjustment, raises concerns.

The Australian study is not an isolated case. Other large observational studies have reported similar associations between diet drinks and diabetes or metabolic disorders:

This was true even after adjusting for body weight and other risk factors (though diet soda’s link to metabolic syndrome components was partly mediated by weight gain).

Systematic reviews of such cohort studies tend to show a small but significant positive association between artificial sweetener intake and diabetes risk, although confidence is often graded as low due to study limitations.

These human studies cannot prove that diet sodas cause diabetes. It is possible, for example, that people predisposed to diabetes (e.g. already overweight) are more likely to switch to diet drinks, which could confound the findings (“reverse causality”).

That said, investigators in the Aussie study explicitly adjusted for body mass index and found the diet-drink link remained significant, suggesting it was not solely due to obesity. Similarly, the US MESA study found the diabetes risk from diet soda was independent of baseline weight or weight change.

Notably, some studies report that when you do adjust for weight, the effect for sugary drinks disappears but the effect for diet drinks does not. One news summary observed: “when body weight was factored in, the link between sugary drinks and type 2 diabetes disappeared – suggesting being overweight was driving that association.

[But] when body weight was factored into the artificial sweetener link, the increased risk was still present”. This pattern hints that diet drinks may influence glucose metabolism or diabetes risk through mechanisms other than simply promoting obesity.

Feeling like sugar cravings get the best of you? Dive into our science-backed breakdown on sugar and cravings to see what really drives them.

How might “zero-calorie” sweeteners raise diabetes risk? Scientists have several hypotheses, though the exact pathways remain unclear:

In short, the biological reasons for the observed link are not fully established. As ScienceAlert noted, “so many known contributors to type 2 diabetes” exist that researchers cannot yet say artificial sweeteners directly cause diabetes.

Indeed, a recent comprehensive review concluded that randomised trials and most systematic reviews have not provided definitive evidence that non-nutritive sweeteners raise diabetes risk.

This ambiguity led WHO to issue a conditional guideline: while the evidence suggests potential harms (like higher diabetes risk), it may be confounded by other factors. WHO therefore recommends reducing sweetener use as a precaution.

Struggling to understand how sugar affects your body? Discover the connection between sugar and insulin resistance in our latest guide.

Health agencies and expert bodies take a cautious stance:

WHO warns this may be due to confounding (“link may be complicated”), but nonetheless suggests that people should aim to reduce sweet tastes altogether.

In summary, while no health agency has banned diet sodas, there is growing caution. WHO’s advice highlights that “non-sugar sweeteners are not essential dietary factors and have no nutritional value” and that their long-term use could be harmful. The consensus message is moderation.

Given this uncertainty, experts now encourage people (especially those at risk of diabetes) to favour water and unsweetened drinks whenever possible. In fact, a recent clinical study presented at the American Diabetes Association meeting found that switching from diet soda to water dramatically improved outcomes for women with type 2 diabetes.

In that trial, 81 overweight/obese diabetic women were randomly assigned to replace their usual post-lunch diet soda with water (while all participants followed a weight-loss program). At 18 months, the water group lost significantly more weight and – most strikingly – 90% of them achieved diabetes remission, compared to only 45% of the diet-soda group.

This underscores the practical point: water is the healthiest drink choice. We embed an image below illustrating this principle.

Even if you enjoy sweet drinks, consider unsweetened options first (sparkling water with lemon, plain tea/coffee, etc.). If you do use artificial sweeteners, use them sparingly.

For diabetic individuals, the take-home is similar: one diet soft drink a day may not be harmless. It’s wise to monitor blood glucose closely and discuss drink choices with your healthcare team. Drinking plenty of water and cutting back on all sweetened beverages (sugar-free or not) is a safe strategy.

Cutting back on diet sodas is a positive step, but it’s just one part of managing blood sugar and long-term health. Vively gives you the tools to see the bigger picture of how your daily choices affect your metabolism.

With Vively you can:

By combining real-time insights from CGM with your personalised Wellness Score, Vively helps you move beyond assumptions about “healthy” alternatives and truly understand what works for your body.

“Many people assume that switching to diet soft drinks is a safe option, but the research shows it may not be that simple. At Vively, we help people move beyond the labels and see how their choices actually affect their body in real time. Our Wellness Score and CGM insights make it easier to spot patterns and build healthier habits that truly support long-term health.” — Charlotte Battle, Accredited Practising Dietitian & Lead Dietitian at Vively

In summary, while diet soft drinks were designed as a lower-risk alternative to sugary sodas, recent research suggests they are not risk-free. Large cohort studies from Australia, Europe and the US consistently report that habitual diet soda consumption is associated with a higher likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes.

The reasons are still under investigation, and causation has not been proven. Nevertheless, the finding is “surprising” to many health professionals. In light of this, health authorities advise caution: the WHO explicitly warns of potential harms (including raised diabetes risk) from long-term sweetener use, and leading experts now encourage water as the primary beverage for those at risk of diabetes.

For the general public and especially people with diabetes, the smart approach is moderation and awareness. Don’t assume “zero calories” means “zero consequences.” Limiting both sugary drinks and diet sodas, and choosing water or unsweetened beverages, is the safest bet for blood sugar control and overall health.

Get irrefutable data about your diet and lifestyle by using your own glucose data with Vively’s CGM Program. We’re currently offering a 20% discount for our annual plan. Sign up here.

Discover how controlling your glucose levels can aid in ageing gracefully. Learn about the latest research that links glucose levels and ageing, and how Vively, a metabolic health app, can help you manage your glucose and age well.

Delve into the concept of mindful eating and discover its benefits, including improved glucose control and healthier food choices. Learn about practical strategies to implement mindful eating in your daily life.

Understand the nuances of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) testing in Australia, the importance of early diagnosis, and the tests used to effectively diagnose the condition. Also, find out when these diagnostic procedures should be considered.