New Year Special - Save up to 40% today with code INTRO100

Choose how you’d like to begin

CGM program

Optimise metabolism in real time with sensors

Advanced Blood Test

Get your baseline health report and personalised plan

In recent years, direct-to-consumer preventive health platforms have surged in popularity among longevity-minded adults. Function Health subscription service co-founded by functional-medicine expert Dr. Mark Hyman—offers one of the most ambitious programs. For $499 or $798 AUD per year, Function Health members begin with a comprehensive blood draw (over 100 biomarkers) and a follow-up panel months later.

According to Function’s own materials, the annual membership includes 100+ lab tests up front, 60+ follow-up tests after 3–6 months, and personalised clinician insights on all out-of-range values. As one news profile explains, clients get two rounds of testing (about 105 tests initially, then ~60 more) so they can track changes over time.

Function Health is structured as a yearly subscription. You order the service online, then visit a partner lab (they use Quest Diagnostics in the US) for the blood draws. The first round of testing actually requires multiple vials of blood—one reviewer noted it took nearly two dozen vials, so Function split it into two short appointments to avoid fainting.

A few days later, results begin arriving in your Function Health portal. Their platform charts each biomarker on a clear graph, letting you see trends in key metrics (e.g. is LDL cholesterol creeping up, is CRP high or normal?).

Every potential issue flagged in your results is accompanied by a clinician’s summary. In practice, this has meant an 8-page report of doctor-written notes and recommendations. For example, one user learned that daily Tylenol use was inflaming her liver enzymes—a finding unlikely on a routine lab.

The platform even includes advanced diagnostics like lipoprotein(a), apolipoprotein B, and other specialised markers that primary care panels often omit. In short, Function Health aims to be a predictive, preventive health monitor—a hub for personal medical data—rather than a one-off lab test.

For $499 or $798 AUD, Function Health provides 100+ lab tests at the start of each year, 60+ follow-up tests 3–6 months later, clinician-written summaries for any abnormal findings, and ongoing access to results tracking.

The test battery is extremely broad. In addition to standard lipid panels and blood sugar, the Function panel covers 16 heart-related biomarkers, multiple thyroid markers, several cancer-screening markers, ~10 immune markers, and dozens of hormone and metabolic measures (11 markers each for male and female hormones, plus markers of stress, liver, kidney, pancreas, etc.). They even report “biological age” based on a proprietary formula.

This far exceeds a normal annual physical (Function claims “5x more tests than an avg physical”).

Function’s online interface is designed to be easy to navigate. Results are plotted over time, so you can compare, for example, your HDL or HbA1c from one year to the next. The company emphasises actionable insights. In a press interview Dr. Hyman stated that Function provides “digestible, actionable insights based on top knowledge experts and thousands of hours of research”.

In practice, each flagged result comes with guidance – e.g. foods to eat or avoid, supplements to consider, or suggestions to consult a specialist. Users also have access to the Function clinician team via the portal if urgent issues arise.

Curious how functional medicine is shaping care in Australia? Check out Vively’s post on functional medicine in Australia.

Many users and proponents highlight the comprehensiveness of the Function test. By measuring so many biomarkers, it can uncover hidden risk factors or deficiencies that a routine check-up might miss.

For example, Function checks iron stores (ferritin) and inflammation (hs-CRP) and thyroid antibodies, which could signal early problems. If you truly want a 360° “snapshot” of your health, Function Health delivers far more data than a standard blood panel. Users appreciate being able to track trends.

One reviewer noted that after the first year they could see how diet or weight loss efforts were actually shifting their numbers. The digital dashboard lets you watch important values (cholesterol, liver enzymes, vitamins) go up or down over successive tests.

Another advantage is the guidance included. Rather than raw lab reports, members receive a structured summary. One satisfied user said the information was explained by Function’s team so she could understand it – “Function has transformed the way my family takes care of themselves,” noting that “Function explained it” when ordinarily the data would require a doctor’s help. Indeed, Function’s clinicians comb through the data to highlight areas of concern. In a Time profile, the author describes how 20 of her biomarkers were flagged out-of-range, and the team gave detailed notes on each one.

For example, high ketones and calcium oxalate in urine prompted dietary advice, and elevated CRP led to a food-priority list. Many users credit the program with catching issues early or motivating them to change habits (one cited patient discovered statin-level cholesterol and sought a cardiologist after seeing Function’s report).

Finally, Function Health is backed by high-profile investors and experts, which lends credibility for some customers. The platform is based on “P4” predictive/preventive medicine, and its design reflects that ethos.

It operates via standard labs (no unconventional testing), and all lab work is done by accredited facilities. Members also point out the convenience: once signed up, you simply go to the nearest Quest lab rather than arranging dozens of different tests on your own.

Curious how hidden inflammation might be affecting your health? Explore Vively’s post on chronic inflammation and CRP, the blood test that reveals it.

Despite these strengths, critics argue Function Health may produce more confusion than clarity. The biggest concern is information overload. With well over 100 results to review, many users report feeling overwhelmed. As one journalist put it, the tests “armed me with information—but I wasn’t sure exactly what to do with it”.

She wondered if her primary doctor would even want to sift through eight pages of data. In fact, doctors caution that patients frequently come in with “pages-thick labs” needing interpretation. A Northwestern physician noted that about half of Function’s panel consists of routine labs, and some metrics may be “too esoteric” to meaningfully act on. For example, Dr. Cheema said he had “to tell you I don’t know what it means to have your basophil count change month to month – I don’t know if anybody does”.

In other words, small fluctuations in certain numbers (potassium, amylase, basophils, etc.) may have no clear health implication. When so many biomarkers can flag “out of range,” critics wonder if the scorecard approach might spur needless anxiety or doctor visits.

User reviews echo these concerns. Some customers praise the depth of data but admit they needed a doctor’s help to interpret it. One user complained that “there is so much information I need to talk to a doctor to understand what it means”.

Others report frustration with the user experience: a few mention technical glitches (the scheduling widget didn’t work smoothly) and even missing test orders. Customer support is another pain point – one reviewer gave a poor rating and described the live chat as a “terrible experience” with long waits and generic replies.

The cost and logistics are further downsides. At $499 or $798 AUD/year, Function Health is not cheap – and it runs on automatic renewal, which some users resent. One Trustpilot reviewer was happy with the blood tests but unhappy that the membership “automatically charge[s] you $499 after your first year,” even if you don’t want to continue.

The service is also limited to the U.S. (and excludes New York/New Jersey due to insurance rules), so it’s not directly available in Australia. All lab visits are done in person, which means at least two clinic trips for the initial testing. Finally, there is a broader medical debate: not all experts agree that such intensive screening yields net benefits for asymptomatic people. Time points out that more tests can lead to incidental findings that are “emotionally and financially taxing”.

In summary, “Function Health” has inspired both excitement and skepticism. Supporters love the comprehensive, preventive approach and say it has uncovered issues no doctor had caught. For example, a recent user review applauded Function for finding problems that her primary doctor missed—“Couldn’t “have asked for a more insightful, data-driven journey” and “I appreciate their clinical team’s credibility”.

On the other hand, detractors feel the test can be confusing and costly. Trustpilot currently shows a mixed rating (about 2.5/5 based on a few dozen reviews) with comments ranging from “great value” to calls of “clunky” service or even “this is fraud at worst” when tests didn’t show up.

Curious how to get a full-body health check in Australia? Explore Vively’s guide on how to get a full body check in Australia.

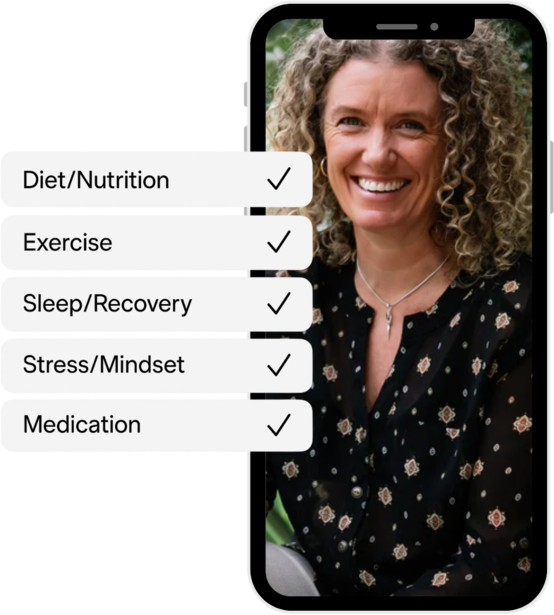

For Australians exploring advanced functional health testing, Vively offers a program designed to go deeper than a one-off assessment. It blends comprehensive biomarker analysis with continuous support, giving you both a clear starting point and the ongoing guidance to act on it.

With Vively, the data becomes actionable — moving beyond test results to a clear, supported plan for long-term wellbeing.

Ready to take charge of your health? Join the Vively waitlist and secure your spot in less than a minute.

The Function Health Test represents a cutting-edge, data-rich approach to preventive care. It delivers far more information than a conventional check-up, and many users find the insights valuable for longevity planning. However, the flip side is that not everyone can easily interpret or act on all this data. Critics warn that “too much information” can be overwhelming and even lead to unnecessary worry.

For Australians interested in this kind of testing, Vively’s blood panel offers the closest equivalent covering dozens of markers and pairing them with an Australian GP’s guidance. If you’re intrigued by this proactive health approach, consider exploring Vively’s program and join the waitlist here: vively.com.au/waitlist. Both options underscore a growing trend: giving individuals ownership of their health data in pursuit of a longer, healthier life.

Subscribe to our newsletter & join a community of 20,000+ Aussies

In recent years, direct-to-consumer preventive health platforms have surged in popularity among longevity-minded adults. Function Health subscription service co-founded by functional-medicine expert Dr. Mark Hyman—offers one of the most ambitious programs. For $499 or $798 AUD per year, Function Health members begin with a comprehensive blood draw (over 100 biomarkers) and a follow-up panel months later.

According to Function’s own materials, the annual membership includes 100+ lab tests up front, 60+ follow-up tests after 3–6 months, and personalised clinician insights on all out-of-range values. As one news profile explains, clients get two rounds of testing (about 105 tests initially, then ~60 more) so they can track changes over time.

Function Health is structured as a yearly subscription. You order the service online, then visit a partner lab (they use Quest Diagnostics in the US) for the blood draws. The first round of testing actually requires multiple vials of blood—one reviewer noted it took nearly two dozen vials, so Function split it into two short appointments to avoid fainting.

A few days later, results begin arriving in your Function Health portal. Their platform charts each biomarker on a clear graph, letting you see trends in key metrics (e.g. is LDL cholesterol creeping up, is CRP high or normal?).

Every potential issue flagged in your results is accompanied by a clinician’s summary. In practice, this has meant an 8-page report of doctor-written notes and recommendations. For example, one user learned that daily Tylenol use was inflaming her liver enzymes—a finding unlikely on a routine lab.

The platform even includes advanced diagnostics like lipoprotein(a), apolipoprotein B, and other specialised markers that primary care panels often omit. In short, Function Health aims to be a predictive, preventive health monitor—a hub for personal medical data—rather than a one-off lab test.

For $499 or $798 AUD, Function Health provides 100+ lab tests at the start of each year, 60+ follow-up tests 3–6 months later, clinician-written summaries for any abnormal findings, and ongoing access to results tracking.

The test battery is extremely broad. In addition to standard lipid panels and blood sugar, the Function panel covers 16 heart-related biomarkers, multiple thyroid markers, several cancer-screening markers, ~10 immune markers, and dozens of hormone and metabolic measures (11 markers each for male and female hormones, plus markers of stress, liver, kidney, pancreas, etc.). They even report “biological age” based on a proprietary formula.

This far exceeds a normal annual physical (Function claims “5x more tests than an avg physical”).

Function’s online interface is designed to be easy to navigate. Results are plotted over time, so you can compare, for example, your HDL or HbA1c from one year to the next. The company emphasises actionable insights. In a press interview Dr. Hyman stated that Function provides “digestible, actionable insights based on top knowledge experts and thousands of hours of research”.

In practice, each flagged result comes with guidance – e.g. foods to eat or avoid, supplements to consider, or suggestions to consult a specialist. Users also have access to the Function clinician team via the portal if urgent issues arise.

Curious how functional medicine is shaping care in Australia? Check out Vively’s post on functional medicine in Australia.

Many users and proponents highlight the comprehensiveness of the Function test. By measuring so many biomarkers, it can uncover hidden risk factors or deficiencies that a routine check-up might miss.

For example, Function checks iron stores (ferritin) and inflammation (hs-CRP) and thyroid antibodies, which could signal early problems. If you truly want a 360° “snapshot” of your health, Function Health delivers far more data than a standard blood panel. Users appreciate being able to track trends.

One reviewer noted that after the first year they could see how diet or weight loss efforts were actually shifting their numbers. The digital dashboard lets you watch important values (cholesterol, liver enzymes, vitamins) go up or down over successive tests.

Another advantage is the guidance included. Rather than raw lab reports, members receive a structured summary. One satisfied user said the information was explained by Function’s team so she could understand it – “Function has transformed the way my family takes care of themselves,” noting that “Function explained it” when ordinarily the data would require a doctor’s help. Indeed, Function’s clinicians comb through the data to highlight areas of concern. In a Time profile, the author describes how 20 of her biomarkers were flagged out-of-range, and the team gave detailed notes on each one.

For example, high ketones and calcium oxalate in urine prompted dietary advice, and elevated CRP led to a food-priority list. Many users credit the program with catching issues early or motivating them to change habits (one cited patient discovered statin-level cholesterol and sought a cardiologist after seeing Function’s report).

Finally, Function Health is backed by high-profile investors and experts, which lends credibility for some customers. The platform is based on “P4” predictive/preventive medicine, and its design reflects that ethos.

It operates via standard labs (no unconventional testing), and all lab work is done by accredited facilities. Members also point out the convenience: once signed up, you simply go to the nearest Quest lab rather than arranging dozens of different tests on your own.

Curious how hidden inflammation might be affecting your health? Explore Vively’s post on chronic inflammation and CRP, the blood test that reveals it.

Despite these strengths, critics argue Function Health may produce more confusion than clarity. The biggest concern is information overload. With well over 100 results to review, many users report feeling overwhelmed. As one journalist put it, the tests “armed me with information—but I wasn’t sure exactly what to do with it”.

She wondered if her primary doctor would even want to sift through eight pages of data. In fact, doctors caution that patients frequently come in with “pages-thick labs” needing interpretation. A Northwestern physician noted that about half of Function’s panel consists of routine labs, and some metrics may be “too esoteric” to meaningfully act on. For example, Dr. Cheema said he had “to tell you I don’t know what it means to have your basophil count change month to month – I don’t know if anybody does”.

In other words, small fluctuations in certain numbers (potassium, amylase, basophils, etc.) may have no clear health implication. When so many biomarkers can flag “out of range,” critics wonder if the scorecard approach might spur needless anxiety or doctor visits.

User reviews echo these concerns. Some customers praise the depth of data but admit they needed a doctor’s help to interpret it. One user complained that “there is so much information I need to talk to a doctor to understand what it means”.

Others report frustration with the user experience: a few mention technical glitches (the scheduling widget didn’t work smoothly) and even missing test orders. Customer support is another pain point – one reviewer gave a poor rating and described the live chat as a “terrible experience” with long waits and generic replies.

The cost and logistics are further downsides. At $499 or $798 AUD/year, Function Health is not cheap – and it runs on automatic renewal, which some users resent. One Trustpilot reviewer was happy with the blood tests but unhappy that the membership “automatically charge[s] you $499 after your first year,” even if you don’t want to continue.

The service is also limited to the U.S. (and excludes New York/New Jersey due to insurance rules), so it’s not directly available in Australia. All lab visits are done in person, which means at least two clinic trips for the initial testing. Finally, there is a broader medical debate: not all experts agree that such intensive screening yields net benefits for asymptomatic people. Time points out that more tests can lead to incidental findings that are “emotionally and financially taxing”.

In summary, “Function Health” has inspired both excitement and skepticism. Supporters love the comprehensive, preventive approach and say it has uncovered issues no doctor had caught. For example, a recent user review applauded Function for finding problems that her primary doctor missed—“Couldn’t “have asked for a more insightful, data-driven journey” and “I appreciate their clinical team’s credibility”.

On the other hand, detractors feel the test can be confusing and costly. Trustpilot currently shows a mixed rating (about 2.5/5 based on a few dozen reviews) with comments ranging from “great value” to calls of “clunky” service or even “this is fraud at worst” when tests didn’t show up.

Curious how to get a full-body health check in Australia? Explore Vively’s guide on how to get a full body check in Australia.

For Australians exploring advanced functional health testing, Vively offers a program designed to go deeper than a one-off assessment. It blends comprehensive biomarker analysis with continuous support, giving you both a clear starting point and the ongoing guidance to act on it.

With Vively, the data becomes actionable — moving beyond test results to a clear, supported plan for long-term wellbeing.

Ready to take charge of your health? Join the Vively waitlist and secure your spot in less than a minute.

The Function Health Test represents a cutting-edge, data-rich approach to preventive care. It delivers far more information than a conventional check-up, and many users find the insights valuable for longevity planning. However, the flip side is that not everyone can easily interpret or act on all this data. Critics warn that “too much information” can be overwhelming and even lead to unnecessary worry.

For Australians interested in this kind of testing, Vively’s blood panel offers the closest equivalent covering dozens of markers and pairing them with an Australian GP’s guidance. If you’re intrigued by this proactive health approach, consider exploring Vively’s program and join the waitlist here: vively.com.au/waitlist. Both options underscore a growing trend: giving individuals ownership of their health data in pursuit of a longer, healthier life.

Get irrefutable data about your diet and lifestyle by using your own glucose data with Vively’s CGM Program. We’re currently offering a 20% discount for our annual plan. Sign up here.

Discover how controlling your glucose levels can aid in ageing gracefully. Learn about the latest research that links glucose levels and ageing, and how Vively, a metabolic health app, can help you manage your glucose and age well.

Delve into the concept of mindful eating and discover its benefits, including improved glucose control and healthier food choices. Learn about practical strategies to implement mindful eating in your daily life.

Understand the nuances of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) testing in Australia, the importance of early diagnosis, and the tests used to effectively diagnose the condition. Also, find out when these diagnostic procedures should be considered.