New Year Special - Save up to 40% today with code INTRO100

Choose how you’d like to begin

CGM program

Optimise metabolism in real time with sensors

Advanced Blood Test

Get your baseline health report and personalised plan

Integrative health (also known as integrative medicine) is an approach that combines conventional Western medicine with evidence-based complementary therapies in a coordinated, whole-person manner. In this view, a patient’s biological, psychological, social and lifestyle factors are all considered together, rather than focusing solely on one disease or organ system.

For example, the U.S. National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) defines integrative health as bringing “conventional and complementary approaches together in a coordinated way… with an emphasis on treating the whole person”.

Similarly, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) describes integrative medicine as reaffirming the practitioner–patient relationship and using “all appropriate therapeutic and lifestyle approaches” (mainstream and complementary) to achieve “optimal health and healing”.

In practice this might mean, for instance, a general practitioner prescribing medication for hypertension alongside recommending yoga, mindfulness or dietary changes to help manage stress and diet.

In contrast, conventional medicine (Western or allopathic medicine) typically uses treatments shown to work in randomised clinical trials (medicines, surgery, etc.) and often focuses on specific diseases or organs.

Alternative medicine generally refers to non-mainstream approaches used instead of conventional treatment (for example, refusing chemotherapy in favour of unproven “natural cures”).

Complementary medicine refers to non-mainstream approaches used in addition to mainstream care. Thus integrative medicine goes a step further by actively coordinating both worlds. As one Australian cancer centre explains, integrative therapies involve “the use of both evidence-based complementary therapies and conventional medicine”.

The idea is not to reject science-based care but to blend it with safe, patient-centred practices like lifestyle changes, stress reduction and natural therapies where appropriate. (It is worth noting that functional medicine – popular in wellness circles – overlaps with this integrative philosophy, though it sometimes operates outside mainstream regulation.)

Want to understand how biological age shows up at the cellular level? Explore our post on DNA methylation tests to learn how they measure the pace of aging.

Integrative health in Australia encompasses a wide range of therapies and modalities. Many of these fall under the category of complementary medicine. According to a national survey, 63.1% of Australian adults had used at least one complementary therapy in the previous year. The most commonly consulted practitioners were manual therapists: for example, 20.7% had seen a massage therapist and 12.6% had seen a chiropractor.

Yoga and meditation are also popular – in the same survey 8.9% of respondents had practised yoga and 15.8% had used relaxation or meditation techniques. Roughly half (47.8%) of people reported using vitamin or mineral supplements, and many take herbal remedies, probiotics or other natural products. In short, “complementary and alternative therapies are estimated to be used by up to two-thirds of people in Australia”.

Most users are female, well-educated, and often managing chronic health issues alongside conventional care.

Common integrative modalities include:

In Australia, acupuncture is a well-established therapy. There are about 4,000 registered acupuncturists under the Chinese Medicine Board (an arm of Australia’s health regulator). Some 10% of Australians have tried acupuncture, and surveys suggest as many as 80% of General Practitioners refer patients for it.

In practice, private health insurers typically offer rebates for acupuncture treatments, and some public hospitals provide it to manage pain or nausea. Traditional Chinese medicine (herbal and acupuncture) is formally regulated: to practise as an “Acupuncturist” or “Chinese medicine practitioner” one must meet university training and registration standards.

Naturopathy is a broad system using herbs, nutrition, lifestyle and other “natural” interventions. It is very popular in Australia, though unlike acupuncture, it is largely unregulated at the national level.

A recent government review describes naturopathy as “a system of healthcare that uses several natural therapy modalities… including herbal medicine and nutritional medicine”. Naturopaths typically give complex herbal formulations, supplements, and detailed lifestyle counselling.

The evidence for naturopathy in specific conditions is still emerging: one 2024 NHMRC review found that naturopathy appeared to benefit patients “for some of the conditions… assessed,” but noted the evidence was low‑certainty. (In practical terms, many people see naturopaths for chronic issues like digestive problems, allergies or fatigue.)

Techniques to calm the mind and body feature prominently in integrative health. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and meditation programs have been adopted by some Australian clinics and wellness providers. One Australian survey of older adults with chronic illness found that while relatively few practised these, a majority who did report them as helpful.

In general population studies, 15–25% report using mindfulness or relaxation techniques for health. Yoga – which combines physical postures, breathing and meditation – is often recommended by integrative practitioners for back pain, mental stress, arthritis and diabetes.

Again, national data show significant uptake: ~9% had practised yoga in the past year. (Many integrative health programs also include tai chi or qi gong for gentle movement and balance.)

Diet and nutrition counselling are central to many integrative approaches. Accredited Practising Dietitians (APDs) work in mainstream healthcare, but integrative nutritionists or nutritional medicine practitioners often advise vitamins, herbal supplements and dietary changes beyond standard medical advice.

For example, one cross-sectional survey found that almost half of Australians (47.8%) used vitamin/mineral supplements as part of their health care. The Australian government regulates vitamin and herbal products as “complementary medicines” (see below), meaning they must be listed or approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration before sale.

Other modalities commonly used include chiropractic and osteopathy (manipulative therapies), remedial massage, aromatherapy, and mind-body practices like hypnotherapy or art therapy. Many psychologists and GPs in Australia now incorporate mind-body techniques or relaxation training into mental health care.

In short, integrative health in Australia is practised through a coalition of providers: some are mainstream doctors and nurses with integrative training, others are dedicated complementary therapists (acupuncturists, naturopaths, etc.), and some are “integrative clinics” that employ teams of both.

For example, the NICM Health Research Institute at Western Sydney University is planning an Integrative Health Centre that will offer GP services alongside yoga therapy, tai chi and acupuncture. Private medical centres also advertise integrative health teams of doctors, nutritionists and traditional therapists (e.g. “medically directed integrative clinics” in major cities).

Curious how prevention and innovation connect with integrative health? Learn more in our post on longevity medicine.

Australia has a mixed regulatory environment for integrative health. The government regulates products like herbs and supplements via the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). The TGA classifies vitamins, minerals, herbal medicines and aromatherapy oils as complementary medicines; these must be entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) as either “listed” or “registered” medicines before sale.

This ensures a basic level of safety and labelling. Unlike registered drugs, listed complementary products do not need the same proof of efficacy, but sponsors must hold evidence of traditional use.

On the practitioner side, some complementary therapies are formally regulated as health professions under Australia’s National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (managed by AHPRA). For example, acupuncturists, chiropractors, osteopaths and Chinese medicine practitioners must have university qualifications and be on a national register (protection of title ensures standards of training).

Dietitians and medical doctors are also registered (and many have extended or “integrative” training). However, many other practitioners are not regulated. Naturopaths, herbalists and meditation or yoga teachers generally have no protected titles – anyone can call themselves a naturopath in most states. Some have formed voluntary registers (e.g. the Australian Register of Naturopaths and Herbalists), but these are not government-run.

Major health organisations have begun to address integrative care. The Australian Medical Association’s 2018 policy on complementary medicine acknowledges that evidence‑based complementary therapies can be part of patient care.

The AMA nonetheless stresses the need for rigorous trials to validate any therapy’s safety and efficacy and warns doctors to inform patients about the evidence and possible interactions. The Cancer Council and Cancer Institute NSW provide guidelines for patients, emphasising that complementary therapies (when used) should support conventional treatment and be evidence-based.

As the NSW Cancer Council puts it, complementary therapies are often used “in conjunction with conventional treatment” to improve well-being, while integrative medicine explicitly means combining “evidence-based complementary therapies and conventional medicine”.

In terms of system integration, Australia has some examples of formal integrative services. Several major cancer hospitals (e.g. at Mater Hospital in Brisbane or NSW cancer centres) offer integrative oncology programs, where patients can see nutritionists, acupuncturists or counsellors alongside oncologists.

Private health insurance often rebates treatments like chiropractic, osteopathy and acupuncture, and some GPs offer “comprehensive health assessments” that include lifestyle advice and naturopathic-style guidance.

On the education front, universities now offer integrative medicine courses: Western Sydney University and Southern Cross University have masters programs, and the RACGP even allows GPs to obtain a qualification in “Extended Skills” for integrative medicine. These developments suggest growing acceptance of integrative approaches in Australia’s healthcare system, provided they meet evidence-based standards.

Looking to see how everyday functioning is measured in integrative care? Explore our post on functional health testing in Australia to understand how ability is assessed as part of holistic health.

Surveys show that use of integrative/complementary medicine is common and enduring in Australia. The landmark 2017 national survey found that 63% of adults had used some form of complementary medicine in the past year. Use has remained consistently high over time, making CAM an “established part of contemporary health management” in Australia.

These figures include everything from taking supplements to seeing a massage therapist. Importantly, most users do not abandon conventional care. In fact, research (the CAMELOT project) shows that many CAM users are people with chronic conditions (like diabetes or heart disease) who use complementary therapies alongside mainstream medicine, not as an alternative.

In other words, integrative health is often chosen by patients who want to add to, rather than replace, their regular treatment.

Why do Australians seek integrative care? Qualitative studies and surveys indicate many reasons: people report wanting a more holistic, personalised approach to their health, dissatisfaction with short GP visits, and a belief in natural or preventative options. For example, a 2013 Australian study found that patients appreciated CAM practitioners for “good listening” and a focus on lifestyle factors, nutrition and mind-body balance.

Many see conventional medicine as “band-aid” symptom control, whereas integrative providers spend more time understanding emotional and lifestyle contributors. Another study of patient views around Western Sydney University’s proposed integrative clinic found people desired exactly that: “greater integration of conventional healthcare with traditional and complementary therapies within a team-based, person-centred environment”.

In practice this means patients want doctors, nurses, psychologists and CAM therapists to communicate and collaborate, so all aspects of health are addressed (mental, social, spiritual as well as physical).

Public attitudes reflect this demand. According to Cancer Institute NSW, the use of complementary therapies is “increasing in Australia, with many people with cancer using them on a regular basis”. Likewise, surveys of the general population show persistently high use: about two-thirds of Australians have tried a vitamin/mineral or herbal supplement, and a majority believe these help them feel better even if cures are not proven.

Women and older Australians are particularly likely to use mind-body therapies (yoga, meditation) for general wellness and stress reduction. Overall, there is a clear trend: integrative health is popular and mainstream among consumers. However, this is not without caution.

The Australian Medical Association and Cancer Council both advise patients to be open with their doctors about any CAM use, so that care can be coordinated safely. For example, the Cancer Council explicitly warns patients to consult their medical team before starting any new supplement or alternative therapy. Such guidance underlines that while Australian public interest in integrative care is strong, healthcare providers stress the importance of evidence and safety.

Want to see how integrative health plays out in everyday wellbeing? Check out our post on holistic health to explore how internal and external factors combine in a whole-person approach.

Integrative approaches often find their strongest application in chronic disease management, mental health, and preventive care. Many Australians with long-term illnesses (diabetes, arthritis, chronic pain, cancer, etc.) turn to integrative therapies to complement standard treatment.

Studies confirm this: one survey found nearly half of patients with type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease had used CAM, spending on average thousands of dollars on visits and supplements. Patients report using nutritional advice, exercise programs, acupuncture, yoga and meditation to help control symptoms (e.g. pain, fatigue, mood) while continuing their prescribed medications.

There is growing evidence for some of these practices. For instance, yoga and tai chi have been linked to improved flexibility and stress relief in patients with arthritis or heart disease, and mindfulness training can reduce anxiety and depression in those with chronic illness.

One Australian meta‑analysis suggests that mindfulness programs may improve blood sugar control and mental well‑being in people with type 2 diabetes. Although more high-quality trials are needed, many patients find that integrative therapies help them feel better and cope with the burdens of illness.

Mental health care has also embraced integrative elements. Mind-body approaches like meditation, deep breathing, and gentle movement are routinely taught in stress and anxiety management workshops. Integrative psychiatrists may combine psychotherapy with nutritional supplements (e.g. omega‑3s), herbal formulas, and physical exercise.

In primary care, GPs increasingly include lifestyle counselling (sleep hygiene, diet, exercise) as part of a holistic mental health plan. In addition, low-cost digital apps and online programs (some run by initiatives like This Way Up, developed in Australia) blend cognitive-behavioural therapy with mindfulness—an integrative model between tech and therapy.

Preventive health is a natural domain for integrative principles. By addressing diet, exercise, sleep, stress and social support, integrative practitioners aim to prevent disease onset before it occurs. Many general practices now offer “lifestyle medicine” clinics where patients get one-on-one coaching on nutrition, smoking cessation and physical activity.

These programs often involve dietitians, exercise physiologists and psychologists working alongside the GP. For example, integrative medicine courses teach clinicians to screen for lifestyle risk factors and use nutritional interventions to prevent diabetes or hypertension. Public interest in wellness means that even healthy individuals seek out preventive integrative care (vitamin therapy, yoga classes, meditation retreats, etc.) to boost immunity and resilience.

Consider the story of Ula, a 48-year-old Queensland mother who was diagnosed with breast cancer. Ula had long preferred natural medicine and gave birth naturally with a midwife. When cancer struck, she sought both conventional oncology and complementary support. Ula saw a naturopath and “integrative doctors” who took a holistic view of her care.

They agreed chemotherapy offered the best chance to cure her cancer, but they also guided her in diet, supplements and yoga. Ula spent thousands of dollars on high-dose vitamin C infusions and herbal supplements alongside chemo. She even started an additional supplement regimen without telling her medical team, feeling guilty about it.

In the end, Ula’s story illustrates the integrative paradigm in microcosm: combining evidence-based cancer treatment with patient-driven complementary therapies. Importantly, her doctors and her naturopath had to coordinate – “the naturopath… was just assuring me that what I was doing was the right thing”.

Health authorities stress that patients like Ula should keep their doctors informed. As the NSW Cancer Council advises: always tell your medical team about any complementary therapy or supplement use, so that the overall plan is safe and effective.

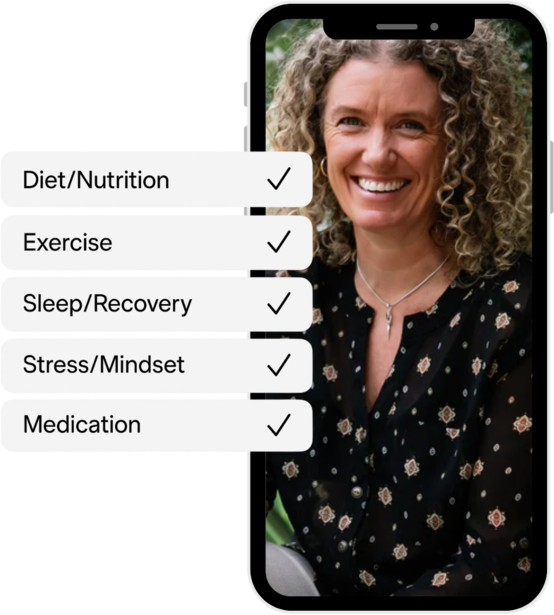

Integrative health is about blending conventional care with evidence-based complementary approaches, and Vively makes that practical by giving you personalised data, expert guidance, and ongoing support. Instead of relying only on one-off visits or guesswork, Vively helps you understand how your body is functioning in real life and what changes will actually move the needle for your health.

With Vively, you can:

“Integrative health works best when patients have the right tools to connect lifestyle, biology and medical care in one clear picture. That’s where Vively can be such a powerful bridge—it empowers people to see how their daily choices shape their long-term wellbeing.” – Dr. Michelle Woolhouse, Integrative GP & Holistic Doctor

By combining advanced diagnostics with daily tracking and personalised coaching, Vively helps you put integrative health into action — moving beyond theory into measurable change.

Ready to experience a more holistic approach to your health? Join the Vively waitlist today! It will only takes 60 seconds to secure your spot.

In summary, integrative health in Australia plays a growing role in managing chronic illness, supporting mental wellness and promoting prevention. By blending the strengths of conventional medicine (e.g. chemotherapy, surgery, psychotropic drugs) with holistic therapies (e.g. acupuncture, mindfulness, nutrition), many Australians seek a more personalised path to health.

This trend is backed by consumer demand—as one study found, patients “desire greater integration of conventional healthcare with traditional and complementary therapies” in a coordinated, team-based model. As long as evidence and safety guide practice, integrative health is increasingly seen not as an “alternative” but as an emerging complement to Australia’s health system.

Subscribe to our newsletter & join a community of 20,000+ Aussies

Integrative health (also known as integrative medicine) is an approach that combines conventional Western medicine with evidence-based complementary therapies in a coordinated, whole-person manner. In this view, a patient’s biological, psychological, social and lifestyle factors are all considered together, rather than focusing solely on one disease or organ system.

For example, the U.S. National Centre for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) defines integrative health as bringing “conventional and complementary approaches together in a coordinated way… with an emphasis on treating the whole person”.

Similarly, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) describes integrative medicine as reaffirming the practitioner–patient relationship and using “all appropriate therapeutic and lifestyle approaches” (mainstream and complementary) to achieve “optimal health and healing”.

In practice this might mean, for instance, a general practitioner prescribing medication for hypertension alongside recommending yoga, mindfulness or dietary changes to help manage stress and diet.

In contrast, conventional medicine (Western or allopathic medicine) typically uses treatments shown to work in randomised clinical trials (medicines, surgery, etc.) and often focuses on specific diseases or organs.

Alternative medicine generally refers to non-mainstream approaches used instead of conventional treatment (for example, refusing chemotherapy in favour of unproven “natural cures”).

Complementary medicine refers to non-mainstream approaches used in addition to mainstream care. Thus integrative medicine goes a step further by actively coordinating both worlds. As one Australian cancer centre explains, integrative therapies involve “the use of both evidence-based complementary therapies and conventional medicine”.

The idea is not to reject science-based care but to blend it with safe, patient-centred practices like lifestyle changes, stress reduction and natural therapies where appropriate. (It is worth noting that functional medicine – popular in wellness circles – overlaps with this integrative philosophy, though it sometimes operates outside mainstream regulation.)

Want to understand how biological age shows up at the cellular level? Explore our post on DNA methylation tests to learn how they measure the pace of aging.

Integrative health in Australia encompasses a wide range of therapies and modalities. Many of these fall under the category of complementary medicine. According to a national survey, 63.1% of Australian adults had used at least one complementary therapy in the previous year. The most commonly consulted practitioners were manual therapists: for example, 20.7% had seen a massage therapist and 12.6% had seen a chiropractor.

Yoga and meditation are also popular – in the same survey 8.9% of respondents had practised yoga and 15.8% had used relaxation or meditation techniques. Roughly half (47.8%) of people reported using vitamin or mineral supplements, and many take herbal remedies, probiotics or other natural products. In short, “complementary and alternative therapies are estimated to be used by up to two-thirds of people in Australia”.

Most users are female, well-educated, and often managing chronic health issues alongside conventional care.

Common integrative modalities include:

In Australia, acupuncture is a well-established therapy. There are about 4,000 registered acupuncturists under the Chinese Medicine Board (an arm of Australia’s health regulator). Some 10% of Australians have tried acupuncture, and surveys suggest as many as 80% of General Practitioners refer patients for it.

In practice, private health insurers typically offer rebates for acupuncture treatments, and some public hospitals provide it to manage pain or nausea. Traditional Chinese medicine (herbal and acupuncture) is formally regulated: to practise as an “Acupuncturist” or “Chinese medicine practitioner” one must meet university training and registration standards.

Naturopathy is a broad system using herbs, nutrition, lifestyle and other “natural” interventions. It is very popular in Australia, though unlike acupuncture, it is largely unregulated at the national level.

A recent government review describes naturopathy as “a system of healthcare that uses several natural therapy modalities… including herbal medicine and nutritional medicine”. Naturopaths typically give complex herbal formulations, supplements, and detailed lifestyle counselling.

The evidence for naturopathy in specific conditions is still emerging: one 2024 NHMRC review found that naturopathy appeared to benefit patients “for some of the conditions… assessed,” but noted the evidence was low‑certainty. (In practical terms, many people see naturopaths for chronic issues like digestive problems, allergies or fatigue.)

Techniques to calm the mind and body feature prominently in integrative health. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and meditation programs have been adopted by some Australian clinics and wellness providers. One Australian survey of older adults with chronic illness found that while relatively few practised these, a majority who did report them as helpful.

In general population studies, 15–25% report using mindfulness or relaxation techniques for health. Yoga – which combines physical postures, breathing and meditation – is often recommended by integrative practitioners for back pain, mental stress, arthritis and diabetes.

Again, national data show significant uptake: ~9% had practised yoga in the past year. (Many integrative health programs also include tai chi or qi gong for gentle movement and balance.)

Diet and nutrition counselling are central to many integrative approaches. Accredited Practising Dietitians (APDs) work in mainstream healthcare, but integrative nutritionists or nutritional medicine practitioners often advise vitamins, herbal supplements and dietary changes beyond standard medical advice.

For example, one cross-sectional survey found that almost half of Australians (47.8%) used vitamin/mineral supplements as part of their health care. The Australian government regulates vitamin and herbal products as “complementary medicines” (see below), meaning they must be listed or approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration before sale.

Other modalities commonly used include chiropractic and osteopathy (manipulative therapies), remedial massage, aromatherapy, and mind-body practices like hypnotherapy or art therapy. Many psychologists and GPs in Australia now incorporate mind-body techniques or relaxation training into mental health care.

In short, integrative health in Australia is practised through a coalition of providers: some are mainstream doctors and nurses with integrative training, others are dedicated complementary therapists (acupuncturists, naturopaths, etc.), and some are “integrative clinics” that employ teams of both.

For example, the NICM Health Research Institute at Western Sydney University is planning an Integrative Health Centre that will offer GP services alongside yoga therapy, tai chi and acupuncture. Private medical centres also advertise integrative health teams of doctors, nutritionists and traditional therapists (e.g. “medically directed integrative clinics” in major cities).

Curious how prevention and innovation connect with integrative health? Learn more in our post on longevity medicine.

Australia has a mixed regulatory environment for integrative health. The government regulates products like herbs and supplements via the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). The TGA classifies vitamins, minerals, herbal medicines and aromatherapy oils as complementary medicines; these must be entered on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG) as either “listed” or “registered” medicines before sale.

This ensures a basic level of safety and labelling. Unlike registered drugs, listed complementary products do not need the same proof of efficacy, but sponsors must hold evidence of traditional use.

On the practitioner side, some complementary therapies are formally regulated as health professions under Australia’s National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (managed by AHPRA). For example, acupuncturists, chiropractors, osteopaths and Chinese medicine practitioners must have university qualifications and be on a national register (protection of title ensures standards of training).

Dietitians and medical doctors are also registered (and many have extended or “integrative” training). However, many other practitioners are not regulated. Naturopaths, herbalists and meditation or yoga teachers generally have no protected titles – anyone can call themselves a naturopath in most states. Some have formed voluntary registers (e.g. the Australian Register of Naturopaths and Herbalists), but these are not government-run.

Major health organisations have begun to address integrative care. The Australian Medical Association’s 2018 policy on complementary medicine acknowledges that evidence‑based complementary therapies can be part of patient care.

The AMA nonetheless stresses the need for rigorous trials to validate any therapy’s safety and efficacy and warns doctors to inform patients about the evidence and possible interactions. The Cancer Council and Cancer Institute NSW provide guidelines for patients, emphasising that complementary therapies (when used) should support conventional treatment and be evidence-based.

As the NSW Cancer Council puts it, complementary therapies are often used “in conjunction with conventional treatment” to improve well-being, while integrative medicine explicitly means combining “evidence-based complementary therapies and conventional medicine”.

In terms of system integration, Australia has some examples of formal integrative services. Several major cancer hospitals (e.g. at Mater Hospital in Brisbane or NSW cancer centres) offer integrative oncology programs, where patients can see nutritionists, acupuncturists or counsellors alongside oncologists.

Private health insurance often rebates treatments like chiropractic, osteopathy and acupuncture, and some GPs offer “comprehensive health assessments” that include lifestyle advice and naturopathic-style guidance.

On the education front, universities now offer integrative medicine courses: Western Sydney University and Southern Cross University have masters programs, and the RACGP even allows GPs to obtain a qualification in “Extended Skills” for integrative medicine. These developments suggest growing acceptance of integrative approaches in Australia’s healthcare system, provided they meet evidence-based standards.

Looking to see how everyday functioning is measured in integrative care? Explore our post on functional health testing in Australia to understand how ability is assessed as part of holistic health.

Surveys show that use of integrative/complementary medicine is common and enduring in Australia. The landmark 2017 national survey found that 63% of adults had used some form of complementary medicine in the past year. Use has remained consistently high over time, making CAM an “established part of contemporary health management” in Australia.

These figures include everything from taking supplements to seeing a massage therapist. Importantly, most users do not abandon conventional care. In fact, research (the CAMELOT project) shows that many CAM users are people with chronic conditions (like diabetes or heart disease) who use complementary therapies alongside mainstream medicine, not as an alternative.

In other words, integrative health is often chosen by patients who want to add to, rather than replace, their regular treatment.

Why do Australians seek integrative care? Qualitative studies and surveys indicate many reasons: people report wanting a more holistic, personalised approach to their health, dissatisfaction with short GP visits, and a belief in natural or preventative options. For example, a 2013 Australian study found that patients appreciated CAM practitioners for “good listening” and a focus on lifestyle factors, nutrition and mind-body balance.

Many see conventional medicine as “band-aid” symptom control, whereas integrative providers spend more time understanding emotional and lifestyle contributors. Another study of patient views around Western Sydney University’s proposed integrative clinic found people desired exactly that: “greater integration of conventional healthcare with traditional and complementary therapies within a team-based, person-centred environment”.

In practice this means patients want doctors, nurses, psychologists and CAM therapists to communicate and collaborate, so all aspects of health are addressed (mental, social, spiritual as well as physical).

Public attitudes reflect this demand. According to Cancer Institute NSW, the use of complementary therapies is “increasing in Australia, with many people with cancer using them on a regular basis”. Likewise, surveys of the general population show persistently high use: about two-thirds of Australians have tried a vitamin/mineral or herbal supplement, and a majority believe these help them feel better even if cures are not proven.

Women and older Australians are particularly likely to use mind-body therapies (yoga, meditation) for general wellness and stress reduction. Overall, there is a clear trend: integrative health is popular and mainstream among consumers. However, this is not without caution.

The Australian Medical Association and Cancer Council both advise patients to be open with their doctors about any CAM use, so that care can be coordinated safely. For example, the Cancer Council explicitly warns patients to consult their medical team before starting any new supplement or alternative therapy. Such guidance underlines that while Australian public interest in integrative care is strong, healthcare providers stress the importance of evidence and safety.

Want to see how integrative health plays out in everyday wellbeing? Check out our post on holistic health to explore how internal and external factors combine in a whole-person approach.

Integrative approaches often find their strongest application in chronic disease management, mental health, and preventive care. Many Australians with long-term illnesses (diabetes, arthritis, chronic pain, cancer, etc.) turn to integrative therapies to complement standard treatment.

Studies confirm this: one survey found nearly half of patients with type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease had used CAM, spending on average thousands of dollars on visits and supplements. Patients report using nutritional advice, exercise programs, acupuncture, yoga and meditation to help control symptoms (e.g. pain, fatigue, mood) while continuing their prescribed medications.

There is growing evidence for some of these practices. For instance, yoga and tai chi have been linked to improved flexibility and stress relief in patients with arthritis or heart disease, and mindfulness training can reduce anxiety and depression in those with chronic illness.

One Australian meta‑analysis suggests that mindfulness programs may improve blood sugar control and mental well‑being in people with type 2 diabetes. Although more high-quality trials are needed, many patients find that integrative therapies help them feel better and cope with the burdens of illness.

Mental health care has also embraced integrative elements. Mind-body approaches like meditation, deep breathing, and gentle movement are routinely taught in stress and anxiety management workshops. Integrative psychiatrists may combine psychotherapy with nutritional supplements (e.g. omega‑3s), herbal formulas, and physical exercise.

In primary care, GPs increasingly include lifestyle counselling (sleep hygiene, diet, exercise) as part of a holistic mental health plan. In addition, low-cost digital apps and online programs (some run by initiatives like This Way Up, developed in Australia) blend cognitive-behavioural therapy with mindfulness—an integrative model between tech and therapy.

Preventive health is a natural domain for integrative principles. By addressing diet, exercise, sleep, stress and social support, integrative practitioners aim to prevent disease onset before it occurs. Many general practices now offer “lifestyle medicine” clinics where patients get one-on-one coaching on nutrition, smoking cessation and physical activity.

These programs often involve dietitians, exercise physiologists and psychologists working alongside the GP. For example, integrative medicine courses teach clinicians to screen for lifestyle risk factors and use nutritional interventions to prevent diabetes or hypertension. Public interest in wellness means that even healthy individuals seek out preventive integrative care (vitamin therapy, yoga classes, meditation retreats, etc.) to boost immunity and resilience.

Consider the story of Ula, a 48-year-old Queensland mother who was diagnosed with breast cancer. Ula had long preferred natural medicine and gave birth naturally with a midwife. When cancer struck, she sought both conventional oncology and complementary support. Ula saw a naturopath and “integrative doctors” who took a holistic view of her care.

They agreed chemotherapy offered the best chance to cure her cancer, but they also guided her in diet, supplements and yoga. Ula spent thousands of dollars on high-dose vitamin C infusions and herbal supplements alongside chemo. She even started an additional supplement regimen without telling her medical team, feeling guilty about it.

In the end, Ula’s story illustrates the integrative paradigm in microcosm: combining evidence-based cancer treatment with patient-driven complementary therapies. Importantly, her doctors and her naturopath had to coordinate – “the naturopath… was just assuring me that what I was doing was the right thing”.

Health authorities stress that patients like Ula should keep their doctors informed. As the NSW Cancer Council advises: always tell your medical team about any complementary therapy or supplement use, so that the overall plan is safe and effective.

Integrative health is about blending conventional care with evidence-based complementary approaches, and Vively makes that practical by giving you personalised data, expert guidance, and ongoing support. Instead of relying only on one-off visits or guesswork, Vively helps you understand how your body is functioning in real life and what changes will actually move the needle for your health.

With Vively, you can:

“Integrative health works best when patients have the right tools to connect lifestyle, biology and medical care in one clear picture. That’s where Vively can be such a powerful bridge—it empowers people to see how their daily choices shape their long-term wellbeing.” – Dr. Michelle Woolhouse, Integrative GP & Holistic Doctor

By combining advanced diagnostics with daily tracking and personalised coaching, Vively helps you put integrative health into action — moving beyond theory into measurable change.

Ready to experience a more holistic approach to your health? Join the Vively waitlist today! It will only takes 60 seconds to secure your spot.

In summary, integrative health in Australia plays a growing role in managing chronic illness, supporting mental wellness and promoting prevention. By blending the strengths of conventional medicine (e.g. chemotherapy, surgery, psychotropic drugs) with holistic therapies (e.g. acupuncture, mindfulness, nutrition), many Australians seek a more personalised path to health.

This trend is backed by consumer demand—as one study found, patients “desire greater integration of conventional healthcare with traditional and complementary therapies” in a coordinated, team-based model. As long as evidence and safety guide practice, integrative health is increasingly seen not as an “alternative” but as an emerging complement to Australia’s health system.

Get irrefutable data about your diet and lifestyle by using your own glucose data with Vively’s CGM Program. We’re currently offering a 20% discount for our annual plan. Sign up here.

Discover how controlling your glucose levels can aid in ageing gracefully. Learn about the latest research that links glucose levels and ageing, and how Vively, a metabolic health app, can help you manage your glucose and age well.

Delve into the concept of mindful eating and discover its benefits, including improved glucose control and healthier food choices. Learn about practical strategies to implement mindful eating in your daily life.

Understand the nuances of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) testing in Australia, the importance of early diagnosis, and the tests used to effectively diagnose the condition. Also, find out when these diagnostic procedures should be considered.