Choose how you’d like to begin

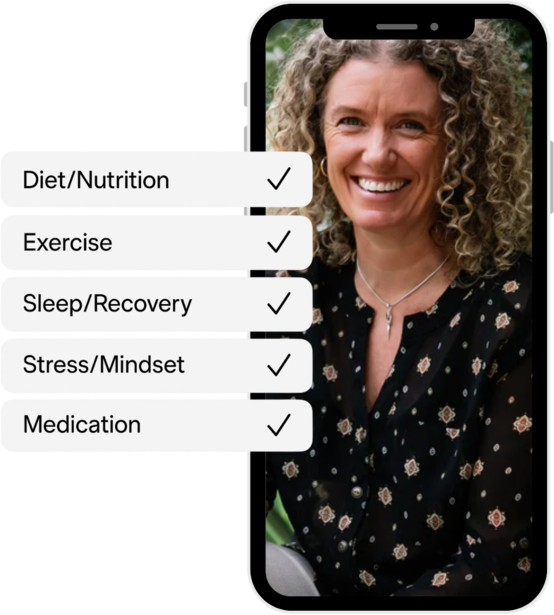

CGM program

Optimise metabolism in real time with sensors

Advanced Blood Test

Get your baseline health report and personalised plan

Fasting means abstaining from food (and often caloric drinks) for a set period. It ranges from daily intermittent schedules (like the “16:8” plan) to longer water-only fasts. For example, the 16:8 regimen involves eating all calories within an 8-hour window and fasting for the remaining 16 hours each day.

Another popular approach is the 5:2 diet, where a person eats normally five days a week and severely restricts calories (about 500–600 kcal) on two non‑consecutive days.

Prolonged fasts (24 hours or longer) are also practised for metabolic health. During a fast, the body shifts from using meal-derived glucose to stored fat and ketones for fuel, and cellular processes like autophagy (the “cleanup” of damaged cells) may be activated.

These methods have become common for weight loss and metabolic improvements, so it’s no surprise that health-conscious fasters often ask: what can I consume without “breaking” my fast?”

Physiologically, a fast is broken when you trigger the fed state again, typically by eating or drinking something that causes a significant insulin/glucose response. Any caloric intake, especially protein or carbohydrates, can activate insulin and halt the fasting metabolism.

For instance, supplements containing protein or sugar (like branched-chain amino acids or gummy vitamins) will provoke an insulin spike and “oppose autophagy”, ending the fast. Pure fats technically contain calories, so strictly speaking they break a fast, but they have minimal insulin effect (thus they may maintain ketosis even after being consumed).

In practice, most fasting guides agree that water, unsweetened coffee or tea (without milk/sugar) are “safe” during a fast, as they have negligible calories and do not raise insulin. Some sources even list very dilute apple cider vinegar in water as acceptable during fasting.

For example, Healthline notes that mixing 5–10 mL (1–2 teaspoons) of ACV with water can help people stay hydrated and stave off hunger without significantly affecting the fast. In short, small amounts of extremely low-calorie, low-carb substances typically do not negate the fasted state.

The main rule is that anything with real calories, sugar, protein, or starch will end a fast by triggering metabolic changes. (For example, a cheeseburger, sweets or even a protein shake would break a fast, whereas plain vinegar or herbal tea generally would not.)

Key point: A fast is usually considered broken by foods or drinks that raise blood glucose/insulin. ACV by itself has only trace calories, so it is generally not thought to break a fast.

Apple cider vinegar (ACV) is simply fermented apple juice. Yeasts first convert apple sugars into alcohol, then acetobacter bacteria turn the alcohol into acetic acid. The end product is mostly water containing about 5–6% acetic acid, along with tiny amounts of minerals and other compounds.

A typical 15 mL (1 tablespoon) of unfiltered ACV has about 3 kcal and roughly 0.1 g carbohydrate (mostly from the trace amounts of residual sugars). It contains virtually no fat or protein. There are also very small amounts of minerals. For example, about 11 mg of potassium per tablespoon and single-digit mg amounts of calcium and magnesium.

Importantly, raw “with mother” ACV contains strands of yeasts and bacteria (“mother”), which may provide probiotics, some B‑vitamins and polyphenol antioxidants. (However, these are in such low quantities that ACV is not a significant source of vitamins or nutrients; UK sources emphasise that it “doesn’t really contain any vitamins or minerals” beyond trivial amounts).

The active ingredient in ACV is acetic acid, which has antimicrobial properties and may influence metabolism. Proponents claim many health benefits for ACV. Nutritionist sources list improved blood sugar control, increased satiety, weight loss support, better cholesterol, and antimicrobial effects among the top claimed benefits.

What does the science say? Some clinical studies do support modest effects. For instance, a 2004 trial found that 20 g of vinegar given with a high-carbohydrate meal significantly lowered post-meal blood glucose levels compared to placebo.

A recent analysis of multiple studies confirms that taking ACV with a starchy meal can slow gastric emptying and blunt the glucose/insulin rise after eating. Similarly, consuming ACV may also modestly improve long-term metabolic markers – a 2023 meta-analysis found that regular ACV intake (typically 1–2 tbsp daily) slightly reduced fasting blood glucose and triglycerides and raised HDL cholesterol.

ACV has also been tested for weight loss. In one Japanese trial, overweight subjects on a calorie-restricted diet who drank 15 mL of ACV with meals daily lost more weight (about 4 kg) over 12 weeks than those who didn’t use vinegar.

Another recent systematic review concluded that ACV can help people feel fuller for longer after meals, which could indirectly aid calorie control. In practice, many people report that a sour ACV drink (especially diluted in water) reduces appetite and cravings between meals. (Note: while weight changes have been observed, all such studies involved dieting and small effects – ACV is not a magic solution, just a minor aid.

In summary, ACV is mostly water and acetic acid, with essentially zero macronutrients. It provides about 3 kcal per tablespoon. It does contain “mother” (probiotic bacteria, enzymes), polyphenols and very small minerals, but these contribute little to nutrition. Some benefits are plausible: research indicates ACV can help lower blood sugar and insulin spikes when used with meals and may increase satiety. It may also modestly improve lipid levels and body weight in the context of a healthy diet.

However, major health claims remain under investigation, and experts urge caution (for example, if you take diabetes medication, the Cleveland Clinic advises checking with a doctor before using ACV daily).

Interested in how a 16:8 fasting schedule might impact your metabolism? Learn more about the metabolic effects of time-restricted eating in our detailed guide.

Because ACV is so low in calories and carbs, it usually does not disrupt the key goals of a fast. One Healthline article notes that one tablespoon of ACV has about 3 calories and <1 g of carbs, so it’s unlikely to affect your fast.

In other words, a spoonful of ACV by itself won’t spike blood sugar or insulin. In fact, the acetic acid in vinegar has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity: studies find that vinegar consumption enhances insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle and lowers post-meal glucose spikes.

Thus, adding a tiny amount of ACV to your water is more likely to stabilise blood sugar than to push you out of ketosis. In summary, experts conclude that ACV’s trace carbs and calories mean it’s “unlikely to negatively affect your fast”.

This is supported by nutrition guides: Healthline’s summary says “ACV contains only trace amounts of carbs and is therefore unlikely to negatively affect your fast,” and notes that it may even help you feel fuller and keep blood sugar steady during a fast.

In contrast, nutrients that definitely break a fast include proteins and starches (which trigger strong insulin/mTOR responses). For example, Healthline notes that branched-chain amino acids will trigger insulin and halt autophagy, whereas pure collagen only “slightly impairs” autophagy.

ACV contains no protein or sugar, so by comparison its impact on autophagy or ketosis is essentially negligible. There is no evidence that diluted vinegar actively reverses autophagy – even if pure water triggers some autophagy, a few calories of ACV won’t shut down that cellular process the way eating a meal would.

In short, ACV is generally considered “fast-friendly”. One Healthline fasting guide explicitly lists 5–10 mL of diluted apple cider vinegar as a permitted fasting beverage, because it may help with cravings without adding significant calories.

Its acidity or enzymes are not known to break the fasted state (unlike protein or sugar). In fact, because it may slow digestion a bit, ACV could help maintain steadier energy levels and prolong ketosis. The consensus from dietitians and clinicians is that small amounts of ACV will not “kick you out” of a fast.

It’s worth noting one more point: dilution. ACV is acidic, so it should always be consumed diluted (e.g. 1–2 tsp in a large glass of water). Drinking it straight can erode tooth enamel and irritate the throat. To be safe, sip ACV-water through a straw or rinse your mouth after. But this is a safety tip, not a fasting issue per se.

Curious about how to prepare for accurate blood sugar results? Read our guide on fasting before a blood sugar test.

In practical terms, the calorie difference between 1 teaspoon (5 mL) and 1 tablespoon (15 mL) of ACV is tiny. About 3 kJ (3 kcal) are in a tablespoon of ACV (some sources list it as 0 calories on nutrition labels, but USDA data shows ~3 cal).

A teaspoon would be roughly 1 kJ (1 cal) or so – effectively negligible. Whether you drink 5 mL or 15 mL of ACV, neither provides enough fuel to meaningfully raise blood sugar or protein levels. The main difference is the amount of acetic acid you’re ingesting: more ACV (1 tbsp) will deliver about three times more acetic acid than a teaspoon. This could, in theory, amplify any biological effect (such as satiety or gastric slowing), but it also increases the risk of side effects.

Expert advice is to use moderate amounts. Healthline recommends that 1–2 tablespoons (15–30 mL) of vinegar per day is sufficient to gain benefits and cautions that “too much” can cause issues like enamel erosion.

In practice, many people start with 1 teaspoon (5 mL) in a cup of water each morning and may work up to 1 tablespoon if tolerated. Either amount is compatible with fasting. A single tablespoon of ACV adds roughly 3 calories – still far below the thresholds (usually ~50 kcal) considered to break a metabolic fast.

Thus, 1 tsp or 1 tbsp of ACV in water are both viewed as safe during a fast. The only caveat is personal tolerance: large doses of ACV on an empty stomach can cause nausea or reflux in some people, so it’s wise to start small.

The impact of ACV during a fast also depends on why you’re fasting. For most common goals, ACV is unlikely to interfere and may even help:

In short, for all fasting goals, small amounts of ACV are largely harmless. It doesn’t meaningfully disrupt weight-loss processes or ketosis, and it may even aid glycaemic control. Only if you are fasting under strict medical supervision (for example, a zero-calorie parenteral fast) would anything other than water be forbidden. Even then, ACV’s impact is so minimal that it would likely go unnoticed.

Curious about the best way to break your fast? Read our complete guide for simple, science-backed strategies.

One extra consideration is ACV’s acidity. Drinking it undiluted or in large amounts can irritate the stomach or damage tooth enamel. This is unrelated to fasting physiology but is important for safe use.

Experts advise always diluting ACV (e.g. 15 mL in at least 250 mL water) and not sipping it too frequently. If you experience heartburn or discomfort, back off or stop ACV. (Interestingly, some people claim ACV eases acid reflux by balancing stomach pH, but the science does not strongly support this.)

Given the above, many dietitians and doctors consider ACV a reasonable addition to a fasting routine, provided you do it correctly. A common recommendation is:

For most healthy individuals, adding a bit of ACV in water during a fast is unlikely to cause harm. It might even help by reducing hunger pangs and stabilizing blood sugar. But it’s not essential – a well-designed fast will succeed without it. Think of ACV as a minor fasting aid, not a requirement.

Fasting can be a powerful tool for weight loss, blood sugar control, and long-term metabolic health—but the reality is that everyone responds differently. While some people experience steady energy and improved glucose balance, others might face dips, cravings, or rebound spikes after eating. Without the right data, it’s difficult to know whether your fasting routine is truly supporting your health goals.

Vively helps bridge that gap by combining continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with personalised insights. Instead of relying on trial and error, you can clearly see how fasting, meal timing, and lifestyle choices are shaping your metabolism. This makes it easier to fine-tune your approach, build sustainable habits, and stay on track.

With Vively, you can:

By pairing fasting practices with Vively’s evidence-based tools, you gain clarity on what’s working, where to adjust, and how to make fasting more effective for your body.

Bottom line: Apple cider vinegar in small, diluted amounts does not appear to break a fast or negate fasting benefits. On the contrary, it may offer slight metabolic and satiety advantages. The consensus from dietitians, doctors and nutrition research is that a splash of ACV in water is fast-friendly. Just use it thoughtfully, stay hydrated, and keep the rest of your fasting plan sound (good nutrition in eating windows and medical guidance if needed).

Subscribe to our newsletter & join a community of 20,000+ Aussies

Fasting means abstaining from food (and often caloric drinks) for a set period. It ranges from daily intermittent schedules (like the “16:8” plan) to longer water-only fasts. For example, the 16:8 regimen involves eating all calories within an 8-hour window and fasting for the remaining 16 hours each day.

Another popular approach is the 5:2 diet, where a person eats normally five days a week and severely restricts calories (about 500–600 kcal) on two non‑consecutive days.

Prolonged fasts (24 hours or longer) are also practised for metabolic health. During a fast, the body shifts from using meal-derived glucose to stored fat and ketones for fuel, and cellular processes like autophagy (the “cleanup” of damaged cells) may be activated.

These methods have become common for weight loss and metabolic improvements, so it’s no surprise that health-conscious fasters often ask: what can I consume without “breaking” my fast?”

Physiologically, a fast is broken when you trigger the fed state again, typically by eating or drinking something that causes a significant insulin/glucose response. Any caloric intake, especially protein or carbohydrates, can activate insulin and halt the fasting metabolism.

For instance, supplements containing protein or sugar (like branched-chain amino acids or gummy vitamins) will provoke an insulin spike and “oppose autophagy”, ending the fast. Pure fats technically contain calories, so strictly speaking they break a fast, but they have minimal insulin effect (thus they may maintain ketosis even after being consumed).

In practice, most fasting guides agree that water, unsweetened coffee or tea (without milk/sugar) are “safe” during a fast, as they have negligible calories and do not raise insulin. Some sources even list very dilute apple cider vinegar in water as acceptable during fasting.

For example, Healthline notes that mixing 5–10 mL (1–2 teaspoons) of ACV with water can help people stay hydrated and stave off hunger without significantly affecting the fast. In short, small amounts of extremely low-calorie, low-carb substances typically do not negate the fasted state.

The main rule is that anything with real calories, sugar, protein, or starch will end a fast by triggering metabolic changes. (For example, a cheeseburger, sweets or even a protein shake would break a fast, whereas plain vinegar or herbal tea generally would not.)

Key point: A fast is usually considered broken by foods or drinks that raise blood glucose/insulin. ACV by itself has only trace calories, so it is generally not thought to break a fast.

Apple cider vinegar (ACV) is simply fermented apple juice. Yeasts first convert apple sugars into alcohol, then acetobacter bacteria turn the alcohol into acetic acid. The end product is mostly water containing about 5–6% acetic acid, along with tiny amounts of minerals and other compounds.

A typical 15 mL (1 tablespoon) of unfiltered ACV has about 3 kcal and roughly 0.1 g carbohydrate (mostly from the trace amounts of residual sugars). It contains virtually no fat or protein. There are also very small amounts of minerals. For example, about 11 mg of potassium per tablespoon and single-digit mg amounts of calcium and magnesium.

Importantly, raw “with mother” ACV contains strands of yeasts and bacteria (“mother”), which may provide probiotics, some B‑vitamins and polyphenol antioxidants. (However, these are in such low quantities that ACV is not a significant source of vitamins or nutrients; UK sources emphasise that it “doesn’t really contain any vitamins or minerals” beyond trivial amounts).

The active ingredient in ACV is acetic acid, which has antimicrobial properties and may influence metabolism. Proponents claim many health benefits for ACV. Nutritionist sources list improved blood sugar control, increased satiety, weight loss support, better cholesterol, and antimicrobial effects among the top claimed benefits.

What does the science say? Some clinical studies do support modest effects. For instance, a 2004 trial found that 20 g of vinegar given with a high-carbohydrate meal significantly lowered post-meal blood glucose levels compared to placebo.

A recent analysis of multiple studies confirms that taking ACV with a starchy meal can slow gastric emptying and blunt the glucose/insulin rise after eating. Similarly, consuming ACV may also modestly improve long-term metabolic markers – a 2023 meta-analysis found that regular ACV intake (typically 1–2 tbsp daily) slightly reduced fasting blood glucose and triglycerides and raised HDL cholesterol.

ACV has also been tested for weight loss. In one Japanese trial, overweight subjects on a calorie-restricted diet who drank 15 mL of ACV with meals daily lost more weight (about 4 kg) over 12 weeks than those who didn’t use vinegar.

Another recent systematic review concluded that ACV can help people feel fuller for longer after meals, which could indirectly aid calorie control. In practice, many people report that a sour ACV drink (especially diluted in water) reduces appetite and cravings between meals. (Note: while weight changes have been observed, all such studies involved dieting and small effects – ACV is not a magic solution, just a minor aid.

In summary, ACV is mostly water and acetic acid, with essentially zero macronutrients. It provides about 3 kcal per tablespoon. It does contain “mother” (probiotic bacteria, enzymes), polyphenols and very small minerals, but these contribute little to nutrition. Some benefits are plausible: research indicates ACV can help lower blood sugar and insulin spikes when used with meals and may increase satiety. It may also modestly improve lipid levels and body weight in the context of a healthy diet.

However, major health claims remain under investigation, and experts urge caution (for example, if you take diabetes medication, the Cleveland Clinic advises checking with a doctor before using ACV daily).

Interested in how a 16:8 fasting schedule might impact your metabolism? Learn more about the metabolic effects of time-restricted eating in our detailed guide.

Because ACV is so low in calories and carbs, it usually does not disrupt the key goals of a fast. One Healthline article notes that one tablespoon of ACV has about 3 calories and <1 g of carbs, so it’s unlikely to affect your fast.

In other words, a spoonful of ACV by itself won’t spike blood sugar or insulin. In fact, the acetic acid in vinegar has been shown to improve insulin sensitivity: studies find that vinegar consumption enhances insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscle and lowers post-meal glucose spikes.

Thus, adding a tiny amount of ACV to your water is more likely to stabilise blood sugar than to push you out of ketosis. In summary, experts conclude that ACV’s trace carbs and calories mean it’s “unlikely to negatively affect your fast”.

This is supported by nutrition guides: Healthline’s summary says “ACV contains only trace amounts of carbs and is therefore unlikely to negatively affect your fast,” and notes that it may even help you feel fuller and keep blood sugar steady during a fast.

In contrast, nutrients that definitely break a fast include proteins and starches (which trigger strong insulin/mTOR responses). For example, Healthline notes that branched-chain amino acids will trigger insulin and halt autophagy, whereas pure collagen only “slightly impairs” autophagy.

ACV contains no protein or sugar, so by comparison its impact on autophagy or ketosis is essentially negligible. There is no evidence that diluted vinegar actively reverses autophagy – even if pure water triggers some autophagy, a few calories of ACV won’t shut down that cellular process the way eating a meal would.

In short, ACV is generally considered “fast-friendly”. One Healthline fasting guide explicitly lists 5–10 mL of diluted apple cider vinegar as a permitted fasting beverage, because it may help with cravings without adding significant calories.

Its acidity or enzymes are not known to break the fasted state (unlike protein or sugar). In fact, because it may slow digestion a bit, ACV could help maintain steadier energy levels and prolong ketosis. The consensus from dietitians and clinicians is that small amounts of ACV will not “kick you out” of a fast.

It’s worth noting one more point: dilution. ACV is acidic, so it should always be consumed diluted (e.g. 1–2 tsp in a large glass of water). Drinking it straight can erode tooth enamel and irritate the throat. To be safe, sip ACV-water through a straw or rinse your mouth after. But this is a safety tip, not a fasting issue per se.

Curious about how to prepare for accurate blood sugar results? Read our guide on fasting before a blood sugar test.

In practical terms, the calorie difference between 1 teaspoon (5 mL) and 1 tablespoon (15 mL) of ACV is tiny. About 3 kJ (3 kcal) are in a tablespoon of ACV (some sources list it as 0 calories on nutrition labels, but USDA data shows ~3 cal).

A teaspoon would be roughly 1 kJ (1 cal) or so – effectively negligible. Whether you drink 5 mL or 15 mL of ACV, neither provides enough fuel to meaningfully raise blood sugar or protein levels. The main difference is the amount of acetic acid you’re ingesting: more ACV (1 tbsp) will deliver about three times more acetic acid than a teaspoon. This could, in theory, amplify any biological effect (such as satiety or gastric slowing), but it also increases the risk of side effects.

Expert advice is to use moderate amounts. Healthline recommends that 1–2 tablespoons (15–30 mL) of vinegar per day is sufficient to gain benefits and cautions that “too much” can cause issues like enamel erosion.

In practice, many people start with 1 teaspoon (5 mL) in a cup of water each morning and may work up to 1 tablespoon if tolerated. Either amount is compatible with fasting. A single tablespoon of ACV adds roughly 3 calories – still far below the thresholds (usually ~50 kcal) considered to break a metabolic fast.

Thus, 1 tsp or 1 tbsp of ACV in water are both viewed as safe during a fast. The only caveat is personal tolerance: large doses of ACV on an empty stomach can cause nausea or reflux in some people, so it’s wise to start small.

The impact of ACV during a fast also depends on why you’re fasting. For most common goals, ACV is unlikely to interfere and may even help:

In short, for all fasting goals, small amounts of ACV are largely harmless. It doesn’t meaningfully disrupt weight-loss processes or ketosis, and it may even aid glycaemic control. Only if you are fasting under strict medical supervision (for example, a zero-calorie parenteral fast) would anything other than water be forbidden. Even then, ACV’s impact is so minimal that it would likely go unnoticed.

Curious about the best way to break your fast? Read our complete guide for simple, science-backed strategies.

One extra consideration is ACV’s acidity. Drinking it undiluted or in large amounts can irritate the stomach or damage tooth enamel. This is unrelated to fasting physiology but is important for safe use.

Experts advise always diluting ACV (e.g. 15 mL in at least 250 mL water) and not sipping it too frequently. If you experience heartburn or discomfort, back off or stop ACV. (Interestingly, some people claim ACV eases acid reflux by balancing stomach pH, but the science does not strongly support this.)

Given the above, many dietitians and doctors consider ACV a reasonable addition to a fasting routine, provided you do it correctly. A common recommendation is:

For most healthy individuals, adding a bit of ACV in water during a fast is unlikely to cause harm. It might even help by reducing hunger pangs and stabilizing blood sugar. But it’s not essential – a well-designed fast will succeed without it. Think of ACV as a minor fasting aid, not a requirement.

Fasting can be a powerful tool for weight loss, blood sugar control, and long-term metabolic health—but the reality is that everyone responds differently. While some people experience steady energy and improved glucose balance, others might face dips, cravings, or rebound spikes after eating. Without the right data, it’s difficult to know whether your fasting routine is truly supporting your health goals.

Vively helps bridge that gap by combining continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) with personalised insights. Instead of relying on trial and error, you can clearly see how fasting, meal timing, and lifestyle choices are shaping your metabolism. This makes it easier to fine-tune your approach, build sustainable habits, and stay on track.

With Vively, you can:

By pairing fasting practices with Vively’s evidence-based tools, you gain clarity on what’s working, where to adjust, and how to make fasting more effective for your body.

Bottom line: Apple cider vinegar in small, diluted amounts does not appear to break a fast or negate fasting benefits. On the contrary, it may offer slight metabolic and satiety advantages. The consensus from dietitians, doctors and nutrition research is that a splash of ACV in water is fast-friendly. Just use it thoughtfully, stay hydrated, and keep the rest of your fasting plan sound (good nutrition in eating windows and medical guidance if needed).

Get irrefutable data about your diet and lifestyle by using your own glucose data with Vively’s CGM Program. We’re currently offering a 20% discount for our annual plan. Sign up here.

Discover how controlling your glucose levels can aid in ageing gracefully. Learn about the latest research that links glucose levels and ageing, and how Vively, a metabolic health app, can help you manage your glucose and age well.

Delve into the concept of mindful eating and discover its benefits, including improved glucose control and healthier food choices. Learn about practical strategies to implement mindful eating in your daily life.

Understand the nuances of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) testing in Australia, the importance of early diagnosis, and the tests used to effectively diagnose the condition. Also, find out when these diagnostic procedures should be considered.